The Football Saga: Dixon’s Dream

The NFL turns 100 years old this year, and the game of football predates that by another 50 or so years, but lots of today’s fans know little about the game prior to the modern Super Bowl era. And that’s a real shame considering how rich and interesting the history of the game is, full of colorful characters and epic events. In this column I hope to share some of that history with you, sharing some of the stories that make up The Football Saga.

The NFL turns 100 years old this year, and the game of football predates that by another 50 or so years, but lots of today’s fans know little about the game prior to the modern Super Bowl era. And that’s a real shame considering how rich and interesting the history of the game is, full of colorful characters and epic events. In this column I hope to share some of that history with you, sharing some of the stories that make up The Football Saga.

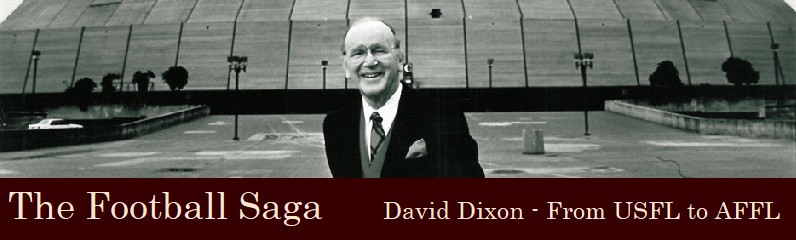

Dixon’s Dream

Despite never having played or coached the game, David Frank Dixon (June 4, 1923 – August 8, 2010) was one of the most influential figures in the history of professional football. Also one of the most interesting. Dixon was an American antique dealer and sports promoter, but more so, he was a true sports visionary who’s passion for the game was the single biggest driving force in bringing the New Orleans Saints and the Louisiana Superdome into existence, and was also the little known architect and founder of the entire USFL experiment. He’s also the father of modern day professional tennis conceiving the concept and then founding World Championship Tennis (WCT) in 1967.

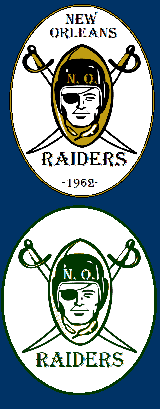

Dixon created the New Orleans Professional Football Club, Inc., in 1962 to lobby for an NFL or an AFL franchise for that city, and almost immediately seemed to find success when the owner of the AFL’s Oakland franchise agreed to sell the Raiders to Dixon for $236,000 after the team finished 1-13 in the 1961 season. Several future Hall of Fame players were on that team that would have become the New Orleans Raiders; however, the mayor of Oakland interceded and helped put a group of investors together to keep the team in Oakland.

As the 1960’s progressed and the looming NFL-AFL merger began to become obvious, Dixon, still trying to bring professional football to New Orleans, used political connections to have members of Congress threaten to hold-up the merger unless the wheels were greased with a New Orleans franchise and the Saints came into being. Then, 2 decades after first conceiving the idea for a giant, domed sports arena in the late 1950’s – long before the Astordome was built – he used some of those same connections and his business acumen to make the Louisiana Superdome a reality.

Unknown to most, it was all the way back in 1965 that Dixon first conceived of and proposed his idea for a football league, called the USFL, that would play its games in the spring rather than the fall. Once the New Orleans Saints were founded, he shelved the idea for almost two decades, but in 1980 he began to revisit the plan. Dixon had studied the strategies and failings of the most recent two challengers to the NFL’s dominance of pro football—the American Football League and the World Football League – for 15 years and finally formed a blueprint for the prospective league’s operations, which became known as The Dixon Plan. The plan included early television exposure, heavy promotion in home markets, and owners with the resources and patience to absorb years of losses—which he felt would be inevitable until the league found its feet. He also assembled a list of prospective franchises located in markets attractive to a potential television partner.

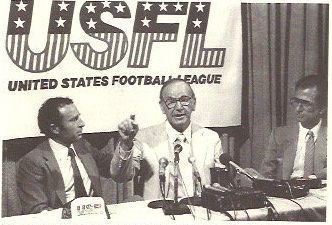

After almost two years of preparation, Dixon founded the USFL and formally announced the league’s formation at the 21 Club in New York City on May 11, 1982, to begin play in 1983. ESPN president Chet Simmons was named the league’s first commissioner in June 1982. With respected college and NFL coach John Ralston as the first employee, Dixon signed up 12 cities—nine in NFL cities and 3 in new markets. The Dixon Plan called for teams in top TV markets to entice the networks into offering the league a TV deal, and all but two of the 12 initial teams were located in the top 13 media markets in the US.

According to The Dixon Plan, if the league was going to be a success, it needed television revenue and exposure, and in 1983, the league signed contracts with both over-the-air broadcaster ABC and a cable TV broadcaster, the then-fledgling ESPN, to televise games. The deals yielded roughly $13 million in 1983 and $16 million in 1984, including $9 million per year from ABC. ABC had options for the 1985 season at $14 million and 1986 at $18 million. Each week, there would be a nationally televised game, as well as the USFL‘s own version of Monday Night Football

At first, the USFL competed with the NFL by following The Dixon Plan which allowed the league to compete not just by playing its games on a March–June schedule during the NFL off-season, but also by having teams play in large NFL caliber stadiums, a tight players’ salary cap of $1.8 million per team (the NFL didn’t introduce a salary cap until 1994), and a territorial draft, to better stock teams with familiar local collegiate stars to help the gate.

The league’s TV revenue met the requirements of The Dixon plan. The Plan called for first year attendance over 18,000 per game, and in 1983, 10 of the 12 teams exceeded that threshold. Securing NFL caliber stadiums, however had proved a not so easy task. Between protectionist NFL franchises and MLB stadium commitments, the USFL ran into numerous problems locating playing fields for some of their new markets, most notably in Boston and San Diego. A contingency plan to locate as many as 4 of the franchises in Canada fell through when the Canadian government moved to protect the CFL legislatively by banning American football teams from locating there. Once play started, the league experienced the beginning of franchise instability, relocation, and closures that almost all pro football leagues, including the NFL, experienced in their early years.

Knowing that a number of past challengers to the NFL had floundered due to financial troubles, Dixon wanted to ensure that USFL teams had the wherewithal to put a credible product on the field. To that end, the league required potential owners to submit to a detailed due diligence and meet strict capitalization requirements. Notably, owners had to post a $1.5 million letter of credit for emergencies. The Dixon Plan also laid out a budget to allow all teams to manage losses in the initial lean years, and emphasized the adherence to a salary cap in order to prevent teams from spending into insolvency.

Owners began deviating from The Plan, almost immediately, beginning with the league’s biggest splash—the signing of Herschel Walker, a three time All-American and the 1982 Heisman Trophy winner to a three-year contract valued at $4.2 million with a $1 million signing bonus. This launched an arms race within the league as the salary cap was circumvented by “personal services contracts” with franchises signing numerous marquee stars. The pursuit of top-level talent proved to be a double-edged sword. While the presence of so many blue-chip stars proved the league could put a competitive product on the field, many teams wildly exceeded the league’s player salary cap in order to put more competitive teams on the field. The Michigan Panthers lost $6 million – three times what Dixon suggested a team could afford to lose in the first season – in the pursuit of becoming the league’s first champions. The desire to compete with other loaded USFL teams and for the league to be seen as approaching NFL caliber led to almost all of the teams exceeding The Dixon Plan‘s team salary cap amount within the league’s first 6 months.

Dixon urged the members of the league to reduce spending, but rather than backing off spending and recommitting to a firmer salary cap, to alleviate the problem, the league sought other options to take on revenue to cover increased cost overruns. These actions magnified the problem. The league added six more teams in 1984 rather than the four initially envisioned by Dixon, to pocket two more expansion fees. This put more pressure on the TV deal, which was not designed to support an 18 team league. The owners then began discussing the possibility of competing head-to-head with the NFL by playing its games in the fall – again, deviating from The Dixon Plan.

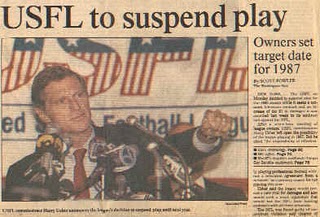

The league’s consulting firm recommended sticking with a spring season, and ABC offered the USFL a 4-year, $175 million TV deal if they would agree to keep playing in the spring while ESPN offered $70M over 3 years. The proponents of a fall schedule argued that if the USFL moved to the fall, it would eventually force a merger with the NFL in which the older league would have to admit at least some USFL teams. The owners in the league walked away from what would have averaged out to $67 million per year in television revenue to pursue victory over the NFL, jettisoning its original model of spring football in favor of the risky gamble of going head-to-head with the NFL.

A frustrated Dixon sold his stake and got out.

The rest, as they say, is history. On August 22, 1984 the owners voted to move to the fall starting in 1986. The Pittsburgh Maulers folded immediately rather than compete with the Pittsburgh Steelers, and the sale of the struggling Washington Federals to a Miami-based ownership group collapsed overnight. The New Orleans Breakers and 1984 champion Philadelphia Stars had to relocate, and the 1983 champion Michigan Panthers surprised the league with an announcement that they would merge with the Oakland Invaders and not be playing in the Detroit area for the 1985 season. Within a few weeks of the vote to move to a fall schedule, the USFL had been forced to abandon four lucrative markets, abort a move to a fifth and suspend operations in a sixth. This destroyed the USFL‘s viability as a league. Several other franchises merged or folded before the 1986 season, and in the end, the league never played a single fall game. The infamous USFL vs NFL lawsuit was just a last ditch effort by some of the remaining owners to capitalize on their investment.

The lawsuit went to a jury trial where the jurors found that the NFL did, in fact, constitute a “duly adjudicated illegal monopoly”, and found that the NFL had willfully “acquired and maintained monopoly status in professional football through predatory tactics.” However, it rejected the USFL‘s other claims and felt that most of its problems were due to its own mismanagement. It awarded the USFL nominal damages of one dollar, which was tripled under antitrust law to three dollars. Once all of the appeals were done, the USFL finally received a check for $3.76 in damages in 1990, the additional 76¢ representing interest earned while litigation had continued (although the NFL also paid over $6 million dollars in court costs and the USFL‘s attorney’s fees. Notably, that check has never been cashed.

The lawsuit went to a jury trial where the jurors found that the NFL did, in fact, constitute a “duly adjudicated illegal monopoly”, and found that the NFL had willfully “acquired and maintained monopoly status in professional football through predatory tactics.” However, it rejected the USFL‘s other claims and felt that most of its problems were due to its own mismanagement. It awarded the USFL nominal damages of one dollar, which was tripled under antitrust law to three dollars. Once all of the appeals were done, the USFL finally received a check for $3.76 in damages in 1990, the additional 76¢ representing interest earned while litigation had continued (although the NFL also paid over $6 million dollars in court costs and the USFL‘s attorney’s fees. Notably, that check has never been cashed.

But what happened to our hero, David Dixon? He never gave up the dream.

Dixon made several attempts to revive his idea of spring football. In 1985, he gave a speech at the Harvard Business School, proposing “America’s Football Teams, Inc.“, a professional league that would sell shares of stock as part of a ticket purchase; after the Fox Television Network was launched in 1987, Dixon proposed the “American Football Federation“, which would have 10 teams and draft academically ineligible high school graduates; and in 1996, Dixon announced the “Fan Ownership Football League“, whose teams would play from July to November and would sell 70 percent of their stock to the general public. None of Dixon’s proposals got beyond the planning stages. In 2008, he published a wildly entertaining autobiography The Saints, The Superdome, and the Scandal: An Insider’s Perspective, and on August 8, 2010, Dixon died from complications from a fall he suffered at his home. He was 87

But the next chapter begins 37 years after the formation of Dixon’s league, with Associated Fantasy and their 2019 launch of their new flagship league, the AFFL. In its brief, 3 season history, through a myriad of mergers and relocations, a total of 19 franchises took the field in Dixon’s USFL, and those 19 franchises will make up AF’s AFFL.

As part of the USFL‘s founding documents, Dixon was entitled to the rights of ownership of his own franchise, which was never established and was sold back to the league when Dixon bailed from the sinking ship in 1984. No record exists of what that team might have become known as. Bringing the story full circle, the 20th franchise will be named the New Orleans Raiders in honor of Dixon’s lifelong pursuit of the football dream and the team he almost brought to his beloved city of New Orleans in 1962. They will adopt the Raiders’ original, 1961 black and gold logo with an alternate logo in the green of Dixon’s hometown alma mater, Tulane University.

Scarlett Grimwood is a southern California native, a UCLA graduate, and former San Diego Chargers cheerleader. She’s an Association veteran, having coached the Little Rock Radio Flyers in The Dixie League, and the Los Angeles Super Chargers in both the World League and Super 16 as well as teams in various AF Tournaments including Scarlett’s Starlets, Dead Red Bed Head, and The Schoolgirl U Lost 2. Currently on a hiatus from fantasy football and living in New Mexico while she pursues a career in wildlife and nature photography, she has agreed to contribute a periodic column – The Football Saga – for Associated Fantasy dedicated to exploring the rich history of the game of football.

Scarlett Grimwood is a southern California native, a UCLA graduate, and former San Diego Chargers cheerleader. She’s an Association veteran, having coached the Little Rock Radio Flyers in The Dixie League, and the Los Angeles Super Chargers in both the World League and Super 16 as well as teams in various AF Tournaments including Scarlett’s Starlets, Dead Red Bed Head, and The Schoolgirl U Lost 2. Currently on a hiatus from fantasy football and living in New Mexico while she pursues a career in wildlife and nature photography, she has agreed to contribute a periodic column – The Football Saga – for Associated Fantasy dedicated to exploring the rich history of the game of football.